Lewis and Clark on the Great Plains A Natural History Chapter 3

South Dakota and North Dakota

Summary of Route and Major Biological Discoveries

Although the extreme southeastern boundary of South Dakota was reached on August 21, 1804, the first actual South Dakota campsite was made on August 23, when the group camped near the present site of Vermillion, South Dakota. On that same day they killed their first bison, near the present site of Ionia, Dixon County. On the 24th they passed a "bluff of blue clay," the so-called Burning Bluffs. The surface of this rocky outcrop was unaccountably warm to the touch, as if it had been burning from within, a phenomenon now believed to have been caused by chemical oxidation. By August 28 the group had reached the present site of Yankton, South Dakota, where they remained until August 31, holding a council with the local Yankton Sioux natives. On September 7 they observed a treeless dome on the south side of the river that they named "The Cupola" (now known as Old Baldy). At the base of this conical dome they discovered a colony of black-tailed prairie dogs, a species then new to science. After the entire group spent most of a day fetching and pouring about five barrels of water down one hole, the resident rodent was finally evicted and caught. Several others were shot and their skins preserved. Some prairie dogs were also eaten during the expedition and were considered fine table fare. Two other members of the prairie-dog community that directly depend on prairie dogs for their own survival, the burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia) and the black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes), were not encountered. The ferret was not discovered and described scientifically for another half-century, but by 1900 it had already been virtually eliminated from North Dakota as well as from most of the Great Plains. It was one of the first Great Plains endemic species to be listed under the Endangered Species Act. The Great Plains race of the burrowing owl was discovered on the plains of western Nebraska in 1820. The rapidly declining burrowing owl may also soon be a candidate for similar nationally threatened or endangered listing.

Map 3. Route of Lewis and Clark in South Dakota

Outward Route Schedule: August 21, 1804, to April 27, 1805

Return Schedule: August 3-5 to September 3, 1806

River Distance: Northernmost Nebraska-South Dakota boundary to present North Dakota-Montana boundary, estimated by Lewis and Clark as 830 miles. Because of recent impoundments and other river alterations, current river distances are substantially less than those encountered by Lewis and Clark.

Map of route of Lewis and Clark in South Dakota

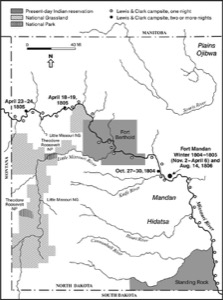

Map 4. Route of Lewis and Clark in North Dakota

Outward Route Schedule: August 21, 1804, to April 27, 1805

Return Schedule: August 3-5 to September 3, 1806

River Distance: Northernmost Nebraska-South Dakota boundary to present North Dakota-Montana boundary, estimated by Lewis and Clark as 830 miles. Because of recent impoundments and other river alterations, current river distances are substantially less than those encountered by Lewis and Clark. Clark estimated the total river distance from their starting point at Camp Wood to the Mandan villages as 1,500 miles, but it actually was closer to 1,600 miles.

Map of route of Lewis and Clark in North Dakota

The expedition left the common boundary of Nebraska and South Dakota on September 8, 1804. Moving north in South Dakota, large herds of bison were seen, as well as elk and deer. They passed the mouth of the White River on September 15, soon encountering "multitudes" of prairie dogs and vast herds of bison and antelope. By September 20 they had reached the Big Bend of the Missouri River, sending two men by horseback across the narrow peninsula to hunt and await their arrival around the enormous bend. Here the first female pronghorn was killed, as well as several mule deer. A coyote was also killed, and was identified as a small species of prairie wolf. On September 24 they reached what they called the "Teton" River (now known as the Bad River, its original English name), so named by the group because of the Teton (Brule) Lakotas who lived along it. Several days were spent interacting with this tribe, including some distinctly unfriendly encounters, and it was not until September 28 that they again departed upstream. They soon passed several abandoned villages of the Arikaras ("Rickaras"), and by October 8 met the first band of that group near the mouth of the Grand River. By the 13th they were on their way again, passing the mouth of Spring Creek (now Campbell County), a short distance below the present North Dakota boundary. That night was their last South Dakota campground, and on October 14 they camped near Blackfoot Creek, virtually on the present North Dakota-South Dakota boundary.

They passed the mouth of North Dakota's Cannonball River on October 18, in what is the present-day Standing Rock Reservation, and on the 19th counted 53 herds of bison and 3 elk herds, all in view at a single time. They soon began to encounter abandoned Mandan villages as well as old Arikara villages. There were also active Awatixa Hidatsa ("Minnetaree") villages in the area, along the Knife River. It was at one of these Hidatsa villages that the teenaged Shoshone woman Sacagawea was living with a French fur trader, Touissant Charbonneau. She had been captured and abducted near Three Forks about five years earlier by the Hidatsas, and had been won by Charbonneau on a wager. On October 26 Lewis and Clark arrived at an active Mandan village site, a location they selected for their winter quarters and named Fort Mandan. Later known as Fort Clark, it was located in what is now the southeastern corner of Mercer County. They were approximately 1,600 river miles up the Missouri from their starting point and roughly halfway across their transcontinental route.

The expedition spent the winter of 1804-5 at Fort Mandan, not departing again until April 7, 1805. At that point the Corps of Discovery consisted of 32 persons. Besides their basic exploratory party of 28 men, they had added 2 interpreters, including Touissant Charbonneau as well as Sacagawea and her infant son, Baptiste, born only about two months previously. The keelboat and its crew of eleven men were sent back to St. Louis, along with many specimens and artifacts that were destined for Washington DC. Among them were live prairie dogs and magpies, 60 preserved plant specimens, a variety of Native American materials, and various skins and skeletons.

The Corps then headed upstream, passing the mouth of the Little Missouri River on April 12 and reaching the mouth of the Yellowstone River on April 26, where they were only a few miles from the present-day boundary of Montana. Between this point and the present boundary, Fort Union was built in 1830 and operated as a frontier trading post for some time before being abandoned. They entered what is now eastern Montana on April 27, 1805, camping just a few miles upstream.

The return trip was much more rapid and far less rewarding in terms of biological discovery. Little time was wasted during this phase, especially after Captain Lewis's narrow escape from eight Blackfoot men during his independent exploration of the upper Marias River of western Montana, together with three of his men. After that hazardous encounter the four men quickly returned to the Missouri River. There they rejoined the rest of their party and continued downstream, reaching the mouth of the Yellowstone River and the approximate boundary of present-day North Dakota on August 7.

This confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers (approximately at the current Montana-North Dakota border) was the agreed-upon rendezvous point for rejoining Captain Clark and his men after their separate route down the Yellowstone River. However, by the time Lewis and his party finally arrived at the planned meeting point, Clark's group had already departed downstream and had left an explanatory note. Lewis and his men thus moved quickly downstream to catch up. Lewis's party finally caught up with that of Captain Clark about 150 miles below the mouth of the Yellowstone River on August 12, 1806, at a location now flooded by Lake Sakakawea but that was probably near Crow Flies High Butte.

The combined Corps then descended the Missouri River in what is now North Dakota. They passed the mouth of the Little Missouri River on August 13, and reached Fort Mandan by the 17th. On August 22 they passed the mouth of the Grand River, and thus were about 25 miles into present-day South Dakota, and on August 25th they passed the mouth of the Cheyenne River. By September 1 they had passed the mouth of the Niobrara River, and had the present-day Nebraska shoreline on their south side. On September 4th they passed the mouth of the Big Sioux River, and were then entirely out of South Dakota and had entered what would eventually become Iowa and Nebraska.

-

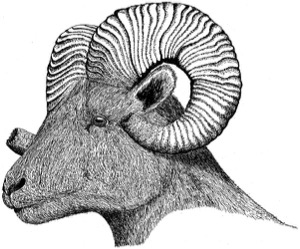

Bighorn Sheep Ovis canadensis auduboni FIG. 9

This species was not encountered until April 26, 1805, at the mouth of the Yellowstone River, where several were seen during a hike a few miles up the Yellowstone. Earlier in Fort Mandan the horns from two animals were obtained, and Captain Clark noted that they were called "rock mountain sheep" by the French. The Great Plains population was later (1901) described as representing a distinct race, and was named by C. Hart Merriam after J. J. Audubon, based on a specimen from the Missouri Valley of South Dakota. It became extinct only a decade or two after it was initially named.

-

Bison Bison bison

As noted earlier, the first large herd of bison was noted on September 9, 1804, near the mouth of the Niobrara River along the Nebraska-South Dakota boundary. Thereafter, bison were present in uncountable numbers on the Dakota plains. On September 17, 1804, near the mouth of the White River, a group of about 3,000 were in view at a single time. Between the vicinity of Bon Homme Island, South Dakota, and the expedition's arrival at Fort Mandan, 35 bison were killed. One more was killed at Fort Mandan in November, and at least 42 more by the middle of December. Only three were killed during the rest of winter at Fort Mandan, and the animals were not mentioned again until the group began their spring ascent up the Missouri. Then, from about 50 miles north of the Little Missouri River, increasing numbers of bison were seen, including "immence herds" of bison, deer, and pronghorns in the vicinity of White Earth River on April 22, 1805.

-

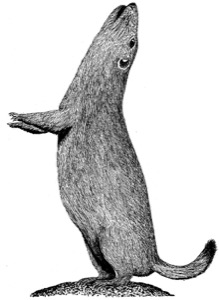

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Cynomys ludovicianus FIG. 10

The black-tailed prairie dog was first described by Lewis and Clark but not formally named as a new species until 1815. As noted earlier, it was discovered somewhat upstream of the mouth of the Niobrara River on September 7, 1804, at a clay promontory the explorers described as "The Tower," located in what is now northern Boyd County. The animals were called "barking squirrels" by Captain Lewis, and prairie dogs (a rough translation of the French petite chien) by Captain Clark. The description by Captain Lewis is highly detailed and accurate; that of Captain Clark is shorter but very interesting. The explorers also saw prairie-dog towns in South Dakota near the White River. These rodents were not specifically mentioned while the expedition was in North Dakota, although the animals are known from later records to have been abundant along the Missouri River, and the four prairie dogs sent back to Washington DC in the spring of l805 from Fort Mandan probably had been captured locally. One of them survived the 4,000-mile journey and was exhibited for a time at Charles W. Peale's Philadelphia Museum, then located in Independence Hall. Prairie dogs were again observed in Montana, including a colony about seven miles in length that was seen in the vicinity of the mouth of the Marias River. At that location a few were killed and eaten, and were found to be "well flavoured and tender." They were also seen near the mouth of the Musselshell River. On the return trip prairie dogs were seen as far south as the vicinity of the Niobrara River, along the South Dakota-Nebraska border, and apparently close to where they had first been discovered.

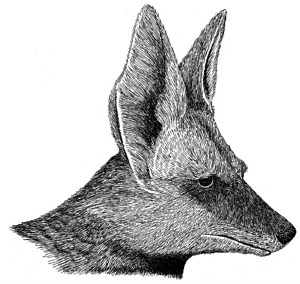

- Coyote Canis latrans FIG. 11 Lewis and Clark deserve credit for discovering that this species is distinct from the larger gray wolf. Captain Clark first mentioned it on September 18, 1804, when a "prairie wolf" said to be the size of a gray fox was shot near the White River of South Dakota. Clark had earlier (August 12, 1804) observed a kind of smaller wolf that "barks like a large ferce dog." It wasn't until the expedition was on the Missouri River the next spring (May 5, 1805) that Clark found a den of young "wolves," and Captain Lewis referred to them as being a "small wolf or burrowing dog of the prairies." Lewis noted their doglike vocalizations, their relatively long and pointed ears, and their unusually long claws. Although the coyote was thus first well described by Lewis and Clark, it was not formally named as a distinct species until 1828.

-

Eastern Cottontail Sylvilagus floridanus

Unidentified rabbits were seen in present-day South Dakota between the Niobrara and White Rivers, near the mouth of the White River, and again in the Big Bend area. These sightings have logically been attributed to the eastern cottontail, although the present-day range of the desert cottontail (S. audubonii) also rather closely approaches the Missouri River in central South Dakota.

-

Gray Wolf Canis lupus FIG. 12

The prairie race (nubilis) of the gray wolf was first described in detail by Lewis and Clark, but it was not formally named until 1823. The gray wolf was apparently first encountered on July 20, 1804, near the mouth of Weeping Water Creek in southeastern Nebraska, when a "large yellow wolf" was killed. On September 21, near the Big Bend of the Missouri in South Dakota, a "white" wolf was shot and skinned. Both wolves and coyotes were seen during the expedition between southeastern Nebraska and the Pacific Coast; both were called "wolves" and often were not distinguished. However, the larger form was sometimes called the "white wolf" and at other times the "large brown wolf." Near Wolf Point, Montana, on May 5, 1805, Captain Lewis described the wolf well, pointing out that it differed from the smaller coyote in not taking refuge in the ground or in a burrow. He also noted that the colors of true wolves varied from blackish brown or gray to creamy white. Wolves were eliminated from Nebraska by 1920, from North Dakota probably during the 1920s, and from South Dakota by 1934, when the last one was killed in the Black Hills. Vagrants have been reported at least three times in North Dakota since 1980.

-

Grizzly Bear Ursus arctos FIG. 2

The grizzly bear was first mentioned by the expedition about 25 miles below the mouth of the Niobrara River, along the Nebraska-South Dakota boundary, where a "White Bear Clift" was named as the site where a grizzly bear had once been killed. Bear tracks were seen on October 7, 1804, on Fox Island, near the mouth of the Moreau River in South Dakota. However, the first actual encounter with a grizzly was on October 20, 1804,when one was wounded near the mouth of the Heart River, just south of present-day Bismarck, North Dakota. Bear tracks of great size were also encountered at the mouth of the Little Missouri River on April 13, 1805. Finally, a grizzly bear was killed by Captain Lewis on April 29 at the mouth of the Yellowstone River, near the Montana border. An even larger male was killed by Captain Clark on May 5; this preserved specimen was the basis for a later formal description and naming (Ursus ferox) of the species. When Prince Maximilian and Audubon visited the Fort Union area 30 and 39 years later, respectively, grizzly bears were still common there. However, grizzly bears were extirpated from South Dakota by about 1890 and from North Dakota by about the end of the nineteenth century. Two were killed near Oakdale, North Dakota, in the autumn of 1897, perhaps representing the last known from that state, or indeed from anywhere within the Great Plains east of Montana.

-

Long-tailed Weasel Mustela frenata

Lewis and Clark did not mention seeing live weasels in the Great Plains, but Captain Lewis purchased a weasel skin at a Mandan village in November 1804. Although weasel skins, especially the white winter-pelage type (ermine), were much prized by Native Americans for their decorative value, they had no real market value for white trappers, and thus no numerical records of early weasel skin harvests are available.

-

(Lynx Felis lynx or Bobcat Felis rufus)

Although bobcats are still common in western North Dakota, there is no record of live bobcats having been encountered by the expedition. Captain Clark mentioned having acquired gloves and a cap made of the skin of a "louservia." Such skins were obtained from the Mandans. Lynxes were also moderately regular in northeastern North Dakota during the early 1800s, but they were often confused with bobcats. Maximilian reported in 1833 that 1,000 to 2,000 lynx skins were brought into Fort Union annually, as well as a similar number of bobcat skins. Vagrant lynx still occasionally wander into northern North Dakota from Canada.

- (Meadow Vole Microtis pennsylvanica)

Rodents, possibly meadow voles, were mentioned by Captain Lewis as gathering seed hordes of "artichokes" (probably Helianthus tuberosus). However, Rueben Thwaites has suggested that these rodents might instead have been "gophers" (his usage presumably referring to ground squirrels rather than true gophers).

-

Mule Deer Odocoileus hemionus FIG. 13

The mule deer was first recognized and accurately described by Lewis and Clark but not formally described until 1817. It was first mentioned on September 5, in the vicinity of the Niobrara River, when the descriptive term "black-tailed deer" was applied to several deer seen by one of the crew members. The first specimen of this species was shot near the mouth of the White River, South Dakota, on September 17, 1804. Captain Clark immediately recognized it to be different from the white-tailed deer, especially in its large and long ears, its more rounded and black-tipped tail, and in its distinctive bounding behavior when frightened. Four more were shot near the Big Bend of the Missouri on September 19, when the equally characteristic symmetrical forking pattern of the species' antlers was also noted by Captain Clark. A much more detailed anatomical description was provided by Captain Lewis on May 10, 1805, when he initially referred to it as a "mule deer," as distinct from the white-tailed or "common deer." Relatively few mule deer were mentioned during the North Dakota phase of the trip. During the return trip mule deer were last noted in the vicinity of the White River, South Dakota.

-

Muskrat Fiber zibethicus

Muskrats were mentioned only briefly in the expedition journals (e.g., August 7, 1805), but in contrast to beaver no special note was made of these familiar and relatively valueless animals, at least as to their pelt values.

-

Northern River Otter Lontra canadensis

River otters were first reported by the expedition in the vicinity of present-day Bismarck on October 22, 1804, when one was killed. It was next noted on April 14, 1805, when one was seen near the mouth of the Little Missouri River in northwestern North Dakota. In 1833 Maximilian reported that 200 to 300 otter skins were brought in annually to Fort Union, and the skins were often used by Native Americans as decorations. By the early 1900s otters had been eliminated from all Nebraska rivers and were very rare in South Dakota and North Dakota. Transplant and release efforts in Nebraska have helped restore that state's population, which is still very small. There have been recent records of otters in four South Dakota counties as well.

-

Porcupine Erethizon dorsatum

A few mentions of the porcupine appear in the journals. Like the muskrat, it was evidently not considered to be of special economic or biological interest. One was killed near present-day Brule City, South Dakota, on September 13, 1804, and others were seen near present-day Poplar, Montana, on May 5, 1805, where a small river was named Porcupine River (now the Poplar River) because of the abundance of porcupines there.

-

Pronghorn Antilocapra americana

The first pronghorn killed during the expedition was obtained near the mouth of the White River in South Dakota on September 14, 1804. This was a male, or "Buck Goat," in Captain Clark's words. He described it fairly well, concluding it to be "more like the Antilope or Gazella of Africa" than like any species of goat. The first female was killed six days later in the Big Bend region of South Dakota. Clark noted the female's smaller size and smaller horns, and that neither sex has a beard. He thought the animals to be "keenly made" and "butifull." Pronghorns were eventually almost extirpated from Nebraska by the early 1900s but have recently become locally reestablished as a result of release programs. They were also barely surviving in the Dakotas by the turn of the twentieth century but have recovered well in those two states.

-

Richardson's Ground Squirrel Spermophilus richardsonii FIG. 14

There is no hard evidence that Lewis and Clark discovered this fairly common Great Plains species, but it is likely that the ground squirrel they observed near the vicinity of present-day Garrison Dam on April 9, 1805, was of this species. The species is still so common in North Dakota that that state has at times been called the "Flickertail State." However, no clear and convincing description of the animal was provided by either Lewis or Clark. The Richardson's ground squirrel was not formally described until 1811.

-

Short-tailed Shrew Blarina brevicauda

Some specimens of "mice" that were shipped from Fort Mandan to President Jefferson were evidently shrews. These were later identified as probably being short-tailed shrews, but the specimens since have been lost.

-

Striped Skunk Mephitis mephitis

The only mention of this species in the Great Plains was a comment made by Lewis as to seeing a "pole-cat" near the mouth of the White River in South Dakota. Another was seen near the mouth of the Musselshell River in Montana on May 25, 1805. The Lakotas honored the skunk for its refusal to retreat in the face of danger, and sometimes their chiefs tied the skins of skunks to their heels to symbolize the fact that they never ran from a battle. Like the badger, wolf, and fox, the skunk possessed special symbolic powers to the tribes of the high plains.

-

(Swift Fox Vulpes velox)

The tiny swift fox was evidently not noticed by Lewis and Clark while they were in North Dakota, but only a few decades later Maximilian reported this species ("prairie foxes") to be common around Fort Clark, and kept one as a pet. Still later, Audubon also found them to be common at both Fort Clark and Fort Union. One that had been captured alive at Fort Clark was presented to Audubon, and he also kept it as a pet, eventually taking it back to his home in New York State. Swift fox skins were worn by men of the Kit Fox Society of the Oglala Sioux, and their fur was additionally used to wrap war lances. Similarly, wolf skins were worn ceremonially by men of the Wolf Society and were also used as camouflage when stalking bison. The Kit Fox Society of the Oglalas was one of the "policing" societies largely concerned with camp life and hunting, whereas the Wolf Society was a war society. However, inherent courage was also a part of the Kit Fox Society, and according to Joseph Brown one of their songs was as follows: "I am a Fox. I am supposed to die. If there is anything difficult, if there is anything dangerous, that is mine to do."

-

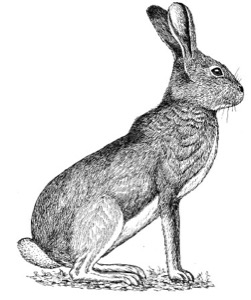

White-tailed Jackrabbit Lepus townsendii FIG. 15

The white-tailed jackrabbit was first described by Lewis and Clark but was not formally described and scientifically named until 1839. Lewis and Clark properly referred to jackrabbits as "hares" rather than rabbits. After collecting the first specimen near the mouth of the White River on September 14, 1804, Captain Clark provided measurements and commented on its white tail. His description thus clearly separates it from the black-tailed jackrabbit (L. californicus) of the same general region, although it now generally occurs farther south. Other sightings of jackrabbits in South Dakota occurred on September 17, 20, and 24, 1804. One was killed at Fort Mandan in January of 1805, and another was obtained in North Dakota the following spring, not far north of Fort Mandan. Jackrabbits were also seen at several Montana sites. One that was shot on May 26, 1805, weighed 8.5 pounds, which is fairly large even for a white-tailed jackrabbit, and is substantially larger than the black-tailed jackrabbit. White-tailed jackrabbits remained common in North Dakota well into the 1900s; during one organized hunt near the town of New England in December of 1924, 7,550 of the animals were killed. This writer remembers community hunts being organized in the Red River Valley of North Dakota into the mid-1930s, during the depression and drought years. White-tailed jackrabbits are now quite rare in the Dakotas and Nebraska.

-

American Crow Corvus brachyrhynchos

Although crows must have been seen frequently across the Great Plains, little note of them was made. In the expedition's Meteorological Register of April 9, 1805, it was noted that crows had returned to Fort Mandan. Crows were also noted in some Montana locations, such as near Great Falls (June 15, 1805) and along the upper Marias River (July 19, 1806). American crow populations have increased significantly in North America during the last four decades, as the birds have benefited from better protection and from adjustments to city life.

-

American Kestrel Falco sparverius

This common and widespread small falcon, traditionally called a "sparrow hawk," was observed in the vicinity of the Little Missouri River on April 13, 1805. It was probably too common and too familiar for Lewis and Clark to have made repeated mention.

-

American Robin Turdus migratorius

Few specific notes were made on this common species. In the expedition's Meteorological Register of April 22, 1805, it was noted that robins had returned to Fort Mandan. Robins were also seen near Great Falls, Montana (June 15, 1805), and on the upper Marias River (July 19, 1806). American robin populations have increased significantly in North America during the last four decades, probably at least in part through increased bird-feeding by humans.

-

Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus

Eagles of unspecified species were noted as far downstream as the vicinity of the mouth of the Niobrara River on September 5, 1806. Bald eagles were first specifically mentioned on April 10, 1805, when they were observed nesting in tall cottonwood trees between Fort Mandan and the Little Missouri River. Other eagle nests were noted on April 25, April 27, and May 7, 1805, near the mouth of the Yellowstone River. On May 8 they were first observed to have young in the nests, and the birds were again seen on August 9 at the mouth of Prairie Creek, near Grayling, Montana. Long on the federally endangered list, the bald eagle has recovered significantly in the past few decades as a result of intensive management efforts, and now breeds in both the Missouri and Yellowstone Valleys of Montana.

-

Bank Swallow Riparia riparia

Captain Clark saw a "vast number" of "a small brown martin" catching insects above Spirit Mound, South Dakota, on August 25, 1804. These were most likely bank swallows but might have included rough-winged swallows (Stelgidopteryx serripennis), which also nest along the steep bluffs of the Missouri River. Both species would have been gathering for fall migration during late August. Bank swallows historically nested in vast numbers on the nearly vertical loess bluffs along the middle Missouri River, from the mouth of the Platte into South Dakota, according to James Ducey. Recent population trends of these species are not clear.

-

Black-billed Magpie Pica pica

Magpies were apparently first seen near the Big Bend of the Missouri and were later found to be winter residents of Fort Mandan. Four living specimens were sent from Fort Mandan to President Jefferson, who in turn passed at least one surviving individual on to Charles W. Peale for exhibit in the Philadelphia Museum. This specimen was later used by Alexander Wilson as the basis for an illustration in his American Ornithology. The species was already well known from Europe, but the American magpie represented a new subspecies. Magpies were also reported in eastern Montana near Fort Union (April 27, 1805) and near Fort Peck (August 3, 1806). Black-billed magpie populations have decreased significantly in North America during the last four decades.

-

Blue Jay Cyanocitta cristata

Although the blue jay is not mentioned in the journals, one of the expedition members informed Wilson (American Ornithology) that the generally ubiquitous blue jay was progressively replaced by the magpie to the north and west of the Big Bend of the Missouri River, where the magpie was first encountered (Reid and Gannon 1999). This same sort of ecological and geographic replacement of the blue jay by the magpie is evident today on the western high plains. Like magpies, blue jay populations have declined significantly in North America during the last four decades, perhaps in part because of competition with the larger American crows.

-

Cedar Waxwing Bombycilla cedrorum

A flock of "cherry or cedar-birds" was seen near Fort Mandan on April 6, 1805, and several were killed. This rather common songbird of the northern forests and riparian woodlands was not mentioned again.

-

Common Poorwill Phalaenoptilus nuttallii FIG. 16

On October 16, 1804, in what is now southern North Dakota, Captain Lewis captured a small bird that he recognized as belonging to the "order of the [blank space; he probably intended "Caprimulgiformes"] or goat sucker." He noted that the bird appeared to be becoming dormant a fact that was not fully established for this or any other North American bird species by ornithologists for another 145 years. Lewis also astutely observed that under the freezing conditions (30 degrees F) the bird could scarcely move, and that even after its heart and lungs were pierced with a knife it remained alive for nearly two hours! Like his later substantiated report of finding Canada geese nesting in trees (probably using old nests of osprey or eagle), this observation was probably not believed by scientists of the time.

-

Common Raven Corvus corax

Ravens wintered in immense numbers in the vicinity of Fort Mandan. They were also seen at various times farther west in Montana, for example, near the present-day sites of Missoula (August 1, 1806) and Lincoln (August 6, 1806) and on the upper Marias River (July 19, 1806). Just as magpies tend to replace blue jays as one proceeds westward in the Great Plains, ravens also tend to replace crows in the same geographic manner. Common raven populations have increased significantly in North America during the last four decades.

-

(Franklin's Gull Larus pipixcan and Forster's Tern Sterna forsteri)

No definite evidence of either of these species appears in the journals, although white gulls were mentioned at various times. On August 7, 1806, near the mouth of the Yellowstone River, Lewis reported flocks of "white gulls about the size of a pigeon, with the top of their heads black." This description might fit the Franklin's gull better than the Forster's tern, since the gull is more likely to migrate in large flocks, and in the summer plumage of the Franklin's gull the entire upper and rear parts of the head are black or dark gray.

-

Golden Eagle Aquila chrysaetos FIG. 17

This is the "grey eagle" of Lewis and Clark, who also at times called it the "beautiful eagle" or "calumet bird." A calumet is the long-stemmed ceremonial pipe used by Native Americans, and the bicolored tail feathers of golden eagles were often used to adorn such pipes. Golden eagles were one of the few birds wintering in the vicinity of Fort Mandan, according to Lewis's notes of April 8, 1805. Several "very large grey" eagles were again seen on July 11, 1805, near Great Falls, Montana. One was also seen at the mouth of the Musselshell River in Montana on August 3, 1806, during the return trip.

-

Great Horned Owl Bubo virginianus

Captain Lewis reported that on April 14, 1805, the group shot a "large hooting owl." He believed it to be more "booted" (an ornithological term meaning that there are feathers on the lower leg or tarsus) and more generally feathered than the eastern form of this species. This is an interesting (albeit incorrect) ornithological point that testifies to Lewis's keen scientific interests.

-

Hairy Woodpecker Picoides villosus or Downy Woodpecker P. pubescens

No specific mention was made of these fairly widespread species. In the expedition's Meteorological Register of February 8, 1805, it was noted that the "black-and-white speckled woodpecker" had returned to Fort Mandan. The larger hairy woodpecker is more likely to be found in North Dakota during February than is the downy, although the downy is perhaps generally somewhat more common than the hairy as a breeding species along the upper Missouri Valley. A hairy or downy woodpecker was also seen upstream from the mouth of the Musselshell River on May 18, 1805, in Montana.

-

Horned Lark Eremophila alpestris

This species, which Captain Clark called the "ren or Prairie burd," was seen in "great numbers" near Spirit Mound in what is now Clay County, South Dakota, on August 25, 1804. This species was also noted to have returned seasonally to western North Dakota by April 10, 1805. Horned larks were again seen near Great Falls, Montana (June 19-25, 1805). They are still among the most common breeding birds of the shortgrass plains and are one of the few likely to overwinter as far north as North Dakota and Montana. Although called a "ren," the bird's seasonal timing and habitats as described by Lewis and Clark do not fit the house wren (Troglodytes aedon). Horned lark populations have decreased significantly in North America during the last four decades as grassland habitats have declined.

-

Killdeer Charadrius vociferus

The "Kildee" was apparently well known to Lewis and Clark but was specifically mentioned only once in the Great Plains region. Lewis noted it on April 8, 1805, in the vicinity of the Knife River in North Dakota.

-

Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus

On April 17, 1805, in northwestern North Dakota, the group saw a "curlue." A "brown curlue" was also noted on April 22, 1805, near the present Montana border. These most probably were long-billed curlews, as the smaller and arctic-nesting whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus) is very rare in Montana. Birds described as curlews were also later seen in Montana during the nesting season, near Great Falls (July 11-13, 1805) and near the present locations of Townsend (July 24, 1805) and Whitehall (August 3, 1805), all within the historic breeding range of long-billed curlews. Long-billed curlew populations have declined significantly in North America during the last four decades; these birds need large areas of native grasslands for breeding.

-

Northern Flicker Colaptes auratus

In Lewis's Meteorological Notes of April 11, 1805, he reported the spring arrival of the well-known "lark-woodpecker." His description perfectly fits the yellow-shafted form of the northern flicker. About four decades later, Audubon encountered flickers that were intermediate in plumage between the eastern yellow-shafted and western red-shafted types, along this same part of the upper Missouri Valley. At the time, the red-shafted was considered a separate species from the yellow-shafted, but they are now regarded as only racially distinct, as a broad zone of intermingled genetic types occurs in this general plains region. Northern flicker populations have declined significantly in North America during the last four decades, as have at least two other woodpecker species.

-

Passenger Pigeon Ectopistes migratorius

This now-extinct but once extremely common pigeon was first mentioned on February 12, 1804, near the mouth of the Missouri River at the start of their trip. Captain Lewis mentioned the birds again near the White River in southern South Dakota on September 16, 1804. They were also seen in west-central Montana on July 12 and 13, 1805, near the mouth of the Sun River, and one was shot by Captain Lewis on the 13th. On the return trip Lewis noted them near Missoula on July 5, 1806, and also along Cut Bank River in northwestern Montana on July 25, 1806. Captain Clark likewise mentioned seeing pigeons along the Yellowstone River on July 25, 1806. These latter sightings may well have involved the band-tailed pigeon (Columba fasciata), as the passenger pigeon is only known with certainty to have occurred in northern Montana. The passenger pigeon was last reported from the Montana region in 1875, from what is now South Dakota in 1884, and from North Dakota in 1892. The last wild birds observed anywhere were seen about 1900, and the last-known individual died in captivity in 1914.

-

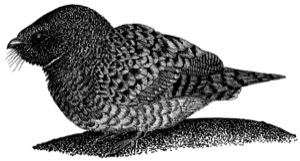

Plains Sharp-tailed Grouse Tympanuchus phasianellus jamesi FIG. 18

Sharp-tailed "grows," also called "pointed tail Prairie fowl" by Captain Clark, were observed to "commence" at the mouth of the James River, and they were seen from "the Big bend upwards." They were observed later at Fort Mandan, North Dakota (February 13, 1805), and again near the mouth of the Little Missouri River in extreme western North Dakota (April 12, 1805). On April 15, 1805, about 50 miles above the mouth of the Little Missouri River and close to the present-day Montana border, a group of displaying males was seen by Captain Lewis. Farther west in Montana sharp-tailed grouse were also seen near the mouth of the Musselshell River (May 21-22, 1805) and near present-day Missoula (July 2, 1806). Lewis and Clark were the first biologists to encounter and mention what are now recognized as the plains (jamesi) and Columbian (columbianus) races of the sharp-tailed grouse. Sharp-tailed grouse of the plains race jamesi still occur over much of the high plains region, although the more western race columbianus is declining as a serious rate and is locally endangered or extirpated in many areas.

-

Snow Goose Chen caerulescens

Captain Lewis reported "great numbers" and "large flocks" of "white brant" on April 9 and 13, 1805, between Fort Mandan and the Little Missouri River, and again on May 5, near Prairie Elk Creek. The ones he described were of the usual white-plumaged morph type; the "gray brant" he described as also present in the flocks might have been young of the previous year or perhaps adults or young of the so-called "blue goose" genetic variant, which are mostly dark grayish brown. He also described a "common brown brant" two-thirds the size of the "common goose" (Canada goose), which might have been one of the smaller races of the Canada goose. The "pided" (pied) brant seen and carefully described later in Oregon was the greater white-fronted goose (Anser albifrons), which also migrates through the Great Plains in large numbers. In Montana snow geese were reportedly seen as far west as the vicinity of Wolf Point (May 5, 1805). Snow goose populations have increased very significantly in North America during the last four decades, largely because they have adjusted their migrations to exploit the protection afforded by wildlife refuges, and are now perhaps more abundant than at any time in American history.

-

Trumpeter Swan Cygnus buccinator FIG. 19

Captain Lewis observed wild swans between Fort Mandan and the Yellowstone River in the spring (April) of 1805. These might have been migrating tundra (previously whistling) swans, but perhaps more likely were trumpeter swans, quasi-permanent residents of the northern plains. Later, Captain Lewis described the whistling swan in some detail, based on his observations in Oregon, and was the first person to call it a "whistleing swan," thus distinguishing it from the "large swan" (trumpeter swan) they had seen earlier on the Great Plains. Lewis thus should be given credit for discovering and first describing the trumpeter swan. Trumpeter swan populations have been recovering in North America as a result of intensive management, and they are no longer on the federal list of endangered species.

-

Western Meadowlark Sturnella neglecta FIG. 20

This bird, later described by Audubon as a new species, was almost certainly what Captain Clark observed in large numbers on the plains around Spirit Mound, now Clay County, near Vermillion, South Dakota, on August 25, 1804. He said the species was about the size of a "partridge" but with a short tail. Captain Lewis later gave an accurate description of a western meadowlark seen near Great Falls, Montana, on June 22, 1805. He contrasted it with the "old field lark" (eastern meadowlark, Sturnella magna) of the Atlantic states, noting the two species' considerable differences in vocalizations and their slight differences in other attributes. The vocal differences noted by Lewis are the most significant distinctions between these two species, and were also mentioned by Audubon when he later described and painted the western meadowlark. Western meadowlarks were also reported near Missoula on July 2, 1806. Their populations have decreased significantly in North America during the last four decades, reflecting losses in grassland habitats.

-

(Western Tanager Piranga ludoviciana)

This species was not mentioned in the expedition journals, but Wilson (American Ornithology) concluded from information reported to him by expedition members that western tanagers "inhabit the extensive plains or prairies of the Missouri, between the Osage and Mandan nations; building their nests in low grass." This must have been a mistaken attribution by Wilson, as neither the habitat nor the nest site fits the ecology of this western forest-dwelling songbird.

-

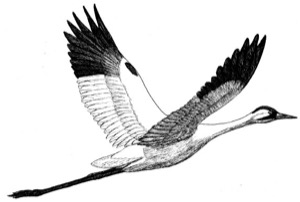

Whooping Crane Grus americana FIG. 21

Near the future site of Fort Berthold, North Dakota, some "large white cranes" were seen passing up the Missouri River on April 11, 1805. They were accurately described as being entirely white except for the larger wing feathers. These currently extremely rare and nationally endangered birds were also reported from western Oregon by Captain Clark, but there is no other evidence that whooping cranes ever occurred that far west, and so this identification seems questionable.

-

Aromatic (Fragrant) Sumac (Squaw bush)

Rhus aromatica, var. trilobata

This is a widespread aromatic shrub whose edible fruits were used as food and for medicinal purposes and teas. The leaves are rich in tannins, and leaf or root extracts were widely used by Native Americans to stop bleeding and for treating a variety of other ailments. Dried leaves often comprised parts of smoking mixtures, which among the Omahas might also contain dogwood (Cornus) bark and Indian tobacco. The flexible green shoots were used for basket-making, and the roots were a source of yellow dye. Collected October 1, 1804, in present-day Stanley County, South Dakota, near the Cheyenne River.

-

Aromatic Aster Aster oblongifolius

This is a widespread native perennial forb. A related species, Aster novaeangliae, was an important medicinal plant for Native Americans, used both externally and internally in the form of teas. Smoke produced from burning it was also believed to help revive an unconscious person. Collected September 21, 1804, in present-day Lyman County, South Dakota, in the Big Bend region.

-

Bearberry (Kinnikinnick) Arctostaphylos uva-ursi FIG. 22

A widespread evergreen shrub of the northern plains and woodlands. The fruits of this species were sometimes cooked and eaten. Its dried leaves were smoked as a substitute for tobacco by many northern tribes of Native Americans, or were mixed in with dogwood bark, tobacco, or other smoking materials. Its Native American name kinnikinnick is from the Algonquian language, probably meaning "a mixture" or "one who mixes," attesting to its widespread use for smoking by Native Americans. Collected during the winter of 1804-5 in present-day McLean County, North Dakota, probably at Fort Mandan.

-

Broom Snakeweed (Broomweed) Gutierrezia sarothrae

A widespread perennial forb. The stems of this species were often used by Native Americans for making brooms, and various parts of the plant were chewed and placed on insect stings or other venomous bites. Its use in treating snakebite is the basis for its vernacular name. The Lakotas boiled the plant to make a tea to treat dizziness and respiratory problems. Collected September 19, 1804, probably in present-day Buffalo County, South Dakota, in the Big Bend region. A newly discovered species.

-

Canada Milk-vetch Astragalus canadensis

This is a widespread perennial legume that, unlike many other species of Astragalus, is nonpoisonous. The Omaha-Ponca tribe used the dried pods as rattles; the Lakotas chewed the roots to relieve chest pains and made a root decoction to treat fever in children. Collected September 15, 1804, probably in present-day Brule County, South Dakota.

-

Creeping Juniper (Shrubby Red Cedar) Juniperus horizontalis

This is a widespread, prostrate evergreen shrub whose cones were used by plains natives to make tea for treating kidney problems. Like the other junipers, its leaves are high in volatile oils. Its fruit is often eaten by birds, which helps spread the seeds. Collected October 16, 1804, probably in present-day Emmons County, North Dakota. A newly discovered species.

-

Dwarf (Common) Juniper Juniperus communis

This is a shrubby evergreen tree that, like all junipers, had many uses by Native Americans, including purification rites and other rituals, as well as for cures. Omaha creation myths associated the juniper with thunder, thunderbirds, or human origins. The twigs possess a strong diuretic component and a volatile oil comprised of monoterpenes. The berrylike fruits were eaten, used as flavorings, or boiled for tea. They are still used as flavoring in gin and in other alcoholic as well as nonalcoholic beverages. Collected October 17, 1804, probably in present-day Sioux County, North Dakota.

-

Dwarf (Silver or Hoary) Sagebrush Artemisia cana

This is a widespread perennial and aromatic shrub that was used by Native Americans for varied medicinal purposes, such as a cough medicine. Lakota men also made bracelets with it for use during the extremely painful sun dance, and both men and women used it to ward off evil influences by burning the plant or drinking tea made from it. Collected October 1 and 2, 1804, probably in present-day Stanley County, South Dakota, near the Cheyenne River, and also the following day, near the Sully-Porter county line. A newly discovered species.

-

False Indigo Amorpha fruticosa

The leaves of this perennial leguminous shrub and other species of Amorpha were used by Native Americans for smoking, making tea, and for medicinal purposes, such as a vermifuge. This plant and the related leadplant (Amorpha canescens) contain cannabinoid substances that might help account for their use in medicines. Collected August 27, 1806, in present-day Lyman or Buffalo County, South Dakota, in the Big Bend region. A newly discovered species.

-

Fire-on-the-Mountain Euphorbia cyathophora

This is a perennial forb that, like other species of its genus, accumulates potent alkaloids in its leaves and elsewhere. The milky sap also contains a variety of toxic diterpenes. Nevertheless, some species of Euphorbia were used by Native Americans for making medicinal teas, these probably serving as purges or emetics. Collected October 15, 1804, probably in present-day Sioux County, North Dakota.

-

Fringed (White) Sagebrush Artemisia ludoviciana FIG. 23

A widespread aromatic subshrub of the arid West that was used by some Native American tribes for varied male ceremonial purposes (thus it was sometimes called "man sage"). It was also used as a medicine for diverse ills, for padding in pillows and saddle pads, and the dried plants were burned to help drive away mosquitoes. Collected October 1, 1804, in present-day Dewey, Sully, or Stanley County, South Dakota, or possibly on April 10, 1806, in present-day Washington or Oregon.

-

Indian ("Rikara") Tobacco Nicotiana quadrivalvus FIG. 24

This non-native forb is a species of tobacco that grows wild from Oregon to California and Nevada, but it evidently migrated east through cultivation by Native Americans, who grew it for smoking. It was cultivated by all the tribes of the Missouri Valley and was greatly favored over the related tobacco species N. rustica, which was widely used by Native peoples from the Mississippi River eastward. All the parts of the plant were dried and smoked, but the dried seed capsules were most prized. The plant matures in 60 to 65 days, and it continues to bear fruit until frost. Collected October 12, 1804, at an Arikara village near the present-day Walworth-Campbell county line, South Dakota. A newly discovered species.

-

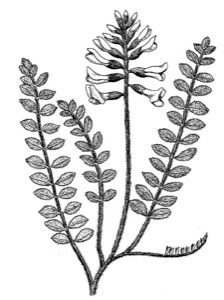

Lanceleaf Sage Salvia reflexa (= "lanceolata") FIG. 25

This is a widespread perennial forb. Its possible use by Native Americans is not clear, but many sages of this genus (not Artemisia) have long been used for cooking spices or as herbal teas. Collected September 21, 1804, in present-day Lyman County, South Dakota. A newly discovered species.

-

Large-flowered Clammyweed Polanisia dodecandra trachysperma

FIG. 26

This annual weedy forb was reportedly collected on August 25, presumably in 1804, when the expedition was in the vicinity of Vermillion (Clay County), South Dakota. The plant is widespread on the Great Plains and is a close relative of Rocky Mountain beeplant. (For its possible medicinal uses by Native Americans, see the entry for Rocky Mountain beeplant in the previous chapter).

-

Long-leaved Sagebrush (Mugwort) Artemisia longifolia

This is a widespread, arid-adapted and aromatic subshrub that, like other species of Artemisia, is aromatic and was similarly used for medicinal purposes. The chewed root was used by men of the Omahas and Winnebagos as a love-charm, by spreading it on their clothing. The Pawnees used a decoction made from these plants for bathing and as a rheumatism treatment. Collected October 3, 1804, in present-day Porter or Sully County, South Dakota, near the Cheyenne River.

-

Missouri Milk-vetch Astragalus missouriensis FIG. 27

This is a widespread perennial legume that, like Canada milk-vetch, is also nonpoisonous. Possible Native American use is not clear, but many of the Astragalus species (especially the locoweeds) are known to have significant adverse physiological effects as a result of toxic alkaloids and/or selenium accumulations. Collected September 18, 1804, in present-day Brule County, South Dakota, near Chamberlain.

-

Pin (Bird) Cherry Prunus pennsylvanica

This cherry was the last plant specimen collected by Captain Lewis, on August 10, 1806, in western North Dakota, and was described in some detail by him on August 12, while he was being treated for a gunshot wound. It has at times been identified as Prunus virginiana.

-

Purple Coneflower Echinacea angustifolia

Although not represented in the herbarium specimens, seeds of what was probably this species were sent to President Jefferson by Captain Lewis, with a comment that this plant is a valuable remedy for snakebite. Nearly all Great Plains tribes used this species medicinally, primarily using macerations of the root, or drinking a tea made from the root as a general painkiller and especially for snakebites. Recent work indicates that oils and polysaccharides are present in the root which have antibiotic, immunostimulatory, and even insecticidal qualities.

-

Rabbitbrush Chrysothamnus nauseosus

(now Ericameria nauseosa)

This widespread perennial shrub of sagelands and shortgrass prairies produces a gummy secretion used for making tea, as a cough syrup, and for chest pains. The dried yellow flowers were also a source of a dye pigment. Collected October 1804, possibly in present-day Dewey or Sully County, South Dakota.

-

Rough Gayfeather (Large Button Snakeroot) Liatris aspera

This widespread perennial forb belongs to a genus often used as medicines by many Native American tribes of the Great Plains. The edible roots were sometimes eaten but were more often used as treatments for a wide array of ailments. Thus, the Pawnees boiled the enlarged root and ate it to treat diarrhea, and the ground flower heads were mixed with corn and fed to horses to increase their endurance. The physiologic basis for these varied medicinal applications is not known, but the traditional use of the root for treating snakebite is the basis for the vernacular English name snakeroot. Collected September 12, 1804, in present-day Brule County, South Dakota.

-

Shadscale (Bushy Atriplex, Four-wing Saltbush)

Atriplex canescens FIG. 28

The abundant seeds of this widespread perennial and alkali-tolerant shrub were ground up and used for bread flour. Collected September 21, 1804, in present-day Lyman County, South Dakota, in the Big Bend region. A newly discovered species.

-

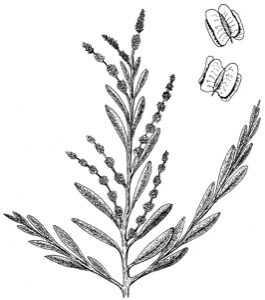

Silky Wormwood (False Tarragon or Linear-leaved Wormwood)

Artemisia dracunculus FIG. 29

This is a widespread perennial and aromatic forb that also occurs in Eurasia. It was used by the Pawnees for treating rheumatism, and its dried stems were used as brooms. All sage species probably contain artemisin and santonin, both lactone glycosides that have vermifuge properties, thus the name "wormwood" has been applied to some species. A terpenelike essential oil, thujone, is also present and may help account for the medicinal effects of sages. Collected September 15, 1804, in present-day Lyman or Brule County, South Dakota, near Chamberlain.

-

Silver-leaf Scurfpea Psoralea (Pediomelum) argophylla

This is a widespread perennial legume. The seeds are poisonous to humans, but the plant is grazed to a slight extent by pronghorns and deer. The Santee Sioux used a decoction for treating horse wounds, and many plains tribes made a tea from its leaves for treating constipation. The ground-up foliage was also mixed with grease and rubbed on the body to treat fever. Collected October 17, 1804, probably in present-day Sioux County, North Dakota, near the Cannonball River. A newly discovered species.

-

Spiny Goldenweed (Cutleaf Ironplant or Sideranthus)

Machaeranthera pinnatifida (Haplopappus spinulosus)

This is a widespread and hardy perennial forb that is highly drought-resistant. Because of its spiny leaves, it is grazed very little by wildlife, and its possible use by Native Americans is unknown. Collected September 15, 1804, in present-day Lyman or Brule County, South Dakota, near Chamberlain. A newly discovered species.

-

Thick-spike Gayfeather (Prairie Button Snakeroot)

Liatris pycnostachya

This is a widespread perennial forb that was eaten and used for medicine by Native Americans. Collected September 15, 1804, probably in present-day Brule County, South Dakota.

-

Western Red Cedar (Rocky Mountain Juniper)

Juniperus scopulorum FIG. 30

A widespread evergreen shrub or small tree. Many western tribes made teas from juniper roots or leaves, or smoked the green twigs, probably for their terpenelike oils. The fruits were eaten raw or cooked, used as flavorings, or ground up and used in cooking. A wax extracted from the berries was also used for making candles. Collected October 2, 1804, probably in present-day Sully or Porter County, South Dakota.

-

White Milkwort Polygala alba

This is a widespread perennial forb widely used by Native Americans for medicinal purposes. For example, the Santee Sioux used it for earaches. A closely related species, P. senega, was used by Native Americans as an antidote for many kinds of poisoning, including snakebites. Collected August 10, 1806, probably in present-day McKenzie County, North Dakota. A newly discovered species.

-

Wild Alfalfa (Few-flowered Psoralea) Psoralidium (Psoralea) tenuiflora

This is a widespread perennial legume. Native Americans made a tea of the stems and leaves as a cure for fever; tea made from the roots was used for treating headaches. The Lakotas burned the roots as a mosquito repellant, and the Santee Sioux boiled the roots to form part of a tuberculosis medicine. Psoralea species produce a substance (psoralin) still under investigation for possible use in several diseases, including immune-system diseases. Collected September 21, 1804, in present-day Lyman County, South Dakota, in the Big Bend region. A newly discovered species.

The closely related breadroot scurfpea (Psoralea esculenta), also called Indian breadfruit or prairie turnip, is widespread in the northern Great Plains and has been described by Kelly Kindscher as "the most important wild food of the Plains Indians." Its root was used by the Blackfoot for making medicinal tea or directly chewed for various ailments. A specimen was collected during the expedition, but the date and location of its collection are questionable. Thus it is given uncertain placement here.