Lewis and Clark on the Great Plains A Natural History Chapter 2

Kansas-Missouri and Nebraska-Iowa

Summary of Route and Major Biological Discoveries

Until the Corps of Discovery reached the vicinity of present-day Kansas (the mouth of the Kansas River) in late June, they had not entered true wilderness and had made only one zoological discovery of interest—their capture on May 31, 1804, of several specimens of the eastern woodrat (Neotoma floridana) in the woods near the mouth of the Osage River, in Osage and Calloway Counties. It was almost another month before they had pushed upstream far enough to reach the Kansas River, near which they saw Carolina parakeets and encountered two villages of Kansa natives.

They reached the present border of Nebraska on July 11, camping near the mouth of the Big Nemaha River on the Nebraska side and the Tarkio River on the Missouri side. By then they were traveling along the so-named bald-pated hills. These tall, loess-formed hills of western Iowa were covered at their lower levels by hardwood forests, but often were capped with native prairie. On July 12, a short distance upstream from the mouth of the Big Nemaha River, they observed some low "artificial" mounds representing the sites of old Native American burial grounds. On the morning of July 30 the group arrived at a high bluff on the Nebraska side that is now part of Fort Calhoun. There they camped for four days and held a council with the assembled chiefs of the Otoe-Missouria tribe. This council was the first held between the natives of the central Missouri Valley and the U.S. government, and the bluff was thus named Council Bluff. It later became the site of Camp Missouri, the first military post in Nebraska, subsequently renamed Fort Calhoun.

On August 13 the group passed Omaha Creek and camped at an old Omaha village that night. On August 16 they seined more than 1,000 fish of at least ten species at this "fishing camp," none of which Elliott Coues could identify with certainty on the basis of the names that the men used. Fish caught in the Nebraska-Iowa region and farther up the Missouri River did include some remarkably large catfish (see the Montana chapter in this book). They remained in the Omaha vicinity until August 19, and then began north again. On August 20, 1804, Sergeant Floyd died of a probable burst appendix and was buried on a high bluff just south of present-day Sioux City, Iowa. The next day the group passed the mouth of the Big Sioux River, camping in what is now Dakota County, Nebraska, with the South Dakota boundary on the opposite shore. The following day (August 22) they passed Ionia Creek and camped in what is now Union County, South Dakota. By September 7 they had passed out of what is now the shoreline of Boyd County, Nebraska, and were then entirely within the present boundaries of South Dakota.

The return trip was relatively rapid, the party arriving in what is now northern Boyd County, Nebraska, on August 29, 1806. They passed the mouths of the Niobrara, James, and Vermillion Rivers on September 1, 2, and 3, respectively. On September 8 they passed Council Bluff, and the next day the mouth of the Platte River. They passed the mouth of the Big Nemaha River and entered present-day Kansas on September 11. On September 15 they passed the mouth of the Kansas River and reentered Missouri. They reached the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers on September 23, 1806, and were finally home.

Map 1. Route of Lewis and Clark in Kansas and Missouri

Outward Route Schedule: June 29 to September 7, 1804

Return Schedule: August 29 to September 15, 1806

River Distance: Mouth of Kansas River to northernmost Nebraska-South Dakota boundary, estimated by Lewis and Clark as 691 river miles. Because of recent channelization and other river changes, the current distance is now substantially less.

Map of route of Lewis and Clark in Kansas and Missouri

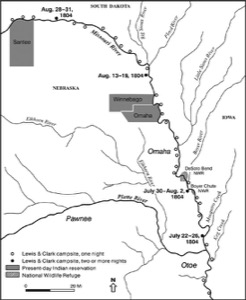

Map 2. Route of Lewis and Clark in Nebraska and Iowa

Outward Route Schedule: June 29 to September 7, 1804

Return Schedule: August 29 to September 15, 1806

River Distance: Mouth of Kansas River to northernmost Nebraska-South Dakota boundary, estimated by Lewis and Clark as 691 river miles. Because of recent channelization and other river changes, the current distance is now substantially less.

Map of route of Lewis and Clark in Nebraska and Iowa

Mammals

-

Badger Taxidea taxus

Near present-day Omaha–Council Bluffs a badger was killed on July 20, 1804. Another was brought into Fort Mandan by one of the party on January 18, 1805. The species was called a "brarow" by the expedition members. The Oglala branch of the Lakotas regarded the badger as having great strength and tenacity, and its symbolic powers extended to the healing of sick children.

-

Beaver Castor canadensis

Beavers were first encountered on the outward journey near present-day Leavenworth, Kansas. They were seen again near Council Bluffs, Iowa, and after that were regularly encountered, being trapped at nearly every stopping point. In Montana alone they were reported from at least 33 locations. In his summary of the natural history of the expedition, Raymond Burroughs calculated that at least 113 beaver were killed over the entire expedition period. Three decades after the Lewis and Clark expedition, Maximilian, Prince of Wied, reported that in a single year 25,000 beaver pelts were brought into Fort Union. Beavers were already becoming rare only a decade later, when John J. Audubon visited the same fort. At the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition, North American beavers were highly valuable as pelts and were classified as the same species as the Old World beaver, but in 1820 they were recognized as separate types. After great overharvesting and near disappearance, the North American beaver has now recovered its former range and may be more common than at any time in the past century.

-

Bison Bison bison FIG. 1

Bison were not encountered by Lewis and Clark until they had nearly reached the mouth of the Kansas River. A large herd of about 500 animals was observed on September 9 above the mouth of the Niobrara River, but none was killed until August 23, when they had they had reached the vicinity of present-day Vermillion, South Dakota. Burroughs calculated that at least 227 bison were killed during the expedition. The last known wild bison, in what is now North Dakota, was killed in 1888, a year after the last one in Montana was killed and about three years after the last Nebraska survivors were eliminated from the North Platte Valley.

-

Black Bear Ursus americanus FIG. 2

Although several black bears were seen in Missouri, none was reported again in journal records until the party arrived in what is now North Dakota, when a female and her cubs were seen near the mouth of the Little Missouri. In a letter to his mother, Captain Lewis mentioned seeing black bears in the Missouri Valley between Kansas and the mouth of the Big Sioux River. Farther west, no black bears were seen by Lewis and Clark between the mouth of the Little Missouri River and the Bitterroot Mountains of Montana, although grizzly bears were very common over this entire route. Burroughs calculated that at least 23 black bears were killed during the expedition. Black bears are now completely gone from Kansas. They are also probably gone from the Missouri Valley of South Dakota (a 1968 Black Hills sighting is the most recent) and from North Dakota (there are some early-twentieth-century records of sightings in the Turtle Mountains). In 2000 a black bear wandered into northwestern Nebraska, perhaps from Wyoming, producing the first state record since 1907. Since then a few more bears have reported in western Nebraska.

-

Eastern Fox Squirrel Sciurus niger

Captain Clark reported that the fox squirrel was seen as far as about 20 miles upstream of the Niobrara River, in what is now extreme northern Nebraska (Boyd County) or adjacent southeastern South Dakota (Charles Mix County). However, fox squirrels were evidently seen to the north, at least to the vicinity of Fort Randall, South Dakota (noted on September 8, 1804).

-

Elk Cervus elaphus FIG. 3

The first elk seen during the outward phase of the expedition was in the vicinity of Nishnabotna Creek, about 70 miles north of present-day St. Joseph, Missouri, along the present-day Kansas-Nebraska border. The first elk was killed when the party reached the vicinity of present-day Fort Calhoun, Nebraska. A second was shot at the mouth of the Little Sioux River, not much farther north, and a third near the mouth of the Niobrara River. From that point onward through the Dakotas and Montana, many more were killed. Burroughs calculated that at least 375 elk were killed during the expedition. On the return trip the last one was obtained near the mouth of the Kansas River. Eventually the elk was extirpated from Nebraska and both Dakotas. By 1877 it was gone from Nebraska, and from South Dakota by 1888. In North Dakota it survived into the 1890s. Captive herds now occur in all three states.

-

Gray Squirrel Sciurus carolinensis

Captain Clark reported that the gray squirrel was found as far north as the mouth of the Little Sioux River, in present-day Iowa (Harrison County) or adjacent Nebraska (Burt County).

-

Pronghorn Antilocapra americana FIG. 4

Pronghorns were accurately described for the first time by Lewis and Clark, but they were not formally described and scientifically named until 1818. They were first observed on September 6, 1804, in the vicinity of the mouth of the Niobrara River. The first one was killed about a week later, in what is now southern South Dakota. Burroughs calculated that at least 62 pronghorns were killed during the expedition. By 1900 the pronghorn population in Nebraska had been reduced to about 100 animals, and by 1925 there were only about 225 in North Dakota. More recently it has recovered somewhat in Nebraska and also in the Dakotas.

-

White-tailed Deer Odocoileus

virginianus

Deer of this common and widespread eastern species were seen from near the start of their expedition north and west to the Three Forks region of Montana. Burroughs calculated that at least 1,001 deer (including mule and black-tailed deer) were killed during the expedition. Deer were rather uniformly taken on the upstream phase from central Missouri to the Montana mountain ranges, and again on the return trip across the Great Plains. Usually the specific identity of the deer killed was not reported, but the expedition provided the first careful descriptions of both the mule deer of the Great Plains and the Pacific-slope black-tailed deer (the two are now considered subspecies). The name "mule deer" was first coined by Captain Lewis.

-

American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus

Captain Clark mentioned that the "Indian hen" was found as far upstream as the mouth of the Little Sioux River, in present-day northwestern Iowa or adjacent Nebraska. The vernacular name "Indian hen" was commonly used for this elusive species through the nineteenth century. Its population numbers have not changed significantly in the past four decades.

-

American White Pelican Pelecanus

erythrorhynchos

On August 8, 1804, the expedition found a flock of several hundred white pelicans resting on a sandbar about two miles north of the mouth of Little Sioux River, in present-day Burt or Thurston County, Nebraska, and Monona County, Iowa. One of these birds was shot and measured by Captain Lewis, and its throat pouch was determined to hold five gallons of water. An estimate of 5,000 to 6,000 birds was made the same day by Private Whitehouse. Pelicans were also seen on the return trip, September 4 and 5, 1806, near the mouth of the Vermillion River, and within the river stretch from present-day Burt to Dixon Counties, Nebraska. A few were also shot on September 6 in what would become southern Burt County. A few white pelicans still use this dredged and highly channelized stretch of the Missouri River during migration to and from their North Dakota or Manitoba breeding grounds, but most migration now occurs in lakes and rivers farther west, where the waters may be clearer and less swift.

-

(Black-bellied Plover Pluvialis

squatarola)

Myron Swenk speculated that some "plovers" seen by Captain Clark on August 15, 1804, in what is now Dakota County might have been migrating black-bellied plovers or perhaps American golden-plovers (Pluvialis dominica). Although both species migrate through Nebraska in autumn, the migration dates for the golden-plover are from early September to late November, and the black-bellied from August to early November. Thus, only the black-bellied would likely have been present in the state during mid-August. Other plover or sandpiper species are also possible candidates; Lewis and Clark apparently applied the term "plover" broadly to shorebirds, not necessarily to plovers specifically.

-

Canada Goose Branta canadensis

Large numbers of Canada geese were encountered between July 13, 1804, along the Richardson County shore, and September 6, 1804, along the present Nebraska–South Dakota boundary. Several of them were killed, including some well-grown goslings. Canada geese were later seen in at least 30 locations in Montana. On the return trip geese were also observed on September 4 and 5, 1806, between present-day Dixon and Burt Counties, Nebraska. Canada goose populations have increased significantly in North America during the last four decades, at least in part because the species is adjusting to the comforts of suburban living.

-

Carolina Parakeet Conuropsis

carolinensis

Captain Clark reported that this beautiful but now-extinct parakeet ("parotqueet") was seen all along the Missouri as far upstream as the Omaha ("Mahar") village, in what is now central Nebraska. Clark had also noted them earlier, near the mouth of the Kansas River, on June 26, 1804. The species was evidently extirpated from Nebraska by 1875 and it was last seen in South Dakota in 1884. The last specimen recorded in Kansas was one shot in 1904. The last known individual of the species died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914, where the last surviving passenger pigeon also died that same year.

-

Cliff Swallow Hirundo pyrrhonota

This species must have been very common on the river during the upstream trip through Nebraska and South Dakota. The birds were seen nesting on July 16, 1804, near Sonora ("Sun") Island in present-day Nemaha County, and nests on a limestone cliff near Blackbird Hill (now Thurston County)were also noted. They were also found nesting along the shoreline of present-day Harrison County, Iowa, on August 5, 1804. Again, on August 22, a large number of nests were seen on a cliff along the shoreline of present-day Dixon County, Nebraska. The species now nests mostly on bridges, especially those made of concrete, which mimic cliff faces closely.

-

Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias

Large numbers of these birds were seen on August 11, 1804, when the party camped on a sandbar above Blackbird Hill in present-day Thurston County, Nebraska. On August 30, 1804, in what is now western Cedar County, Nebraska, one tried to land on the mast of their keelboat and was captured. It was subsequently given to the local tribe of Yankton Sioux. Great blue heron populations have increased significantly in North America during the last four decades, perhaps in part because of improved protection of breeding colonies.

-

Great Egret Ardea alba

A specimen of this egret was shot on August 2, 1804, at the site of present-day Fort Calhoun, Washington County. Great egrets have not historically nested along this stretch of the Missouri, but individual birds now often appear in late summer, after the breeding season. Like great blue herons, great egret populations have increased significantly in North America during the last four decades.

-

Greater Prairie-chicken Tympanuchus cupido

pinnatus

Captain Clark referred to this species as "the Prairie fowl common to the Illinois" and said that its range extended as far north as the mouth of the James River, above which the sharp-tailed species occurred. The farthest point north at which Captain Clark saw the birds thus may have been in present-day Cedar County, Nebraska, or across the river on the South Dakota side near present-day Yankton. This interior race of the greater prairie-chicken is closely related to the now-extinct Atlantic coast race of prairie-chicken, which was called the heath hen (T. c. cupido). The interior race pinnatus thrived during the late 1800s as the fertile lands of the tallgrass prairies were initially opened to small-grain agriculture, but the population collapsed only a few decades later as natural breeding habitats became increasingly rare. The interior race has long been extirpated from the immediate Missouri Valley of Nebraska, but it does still occur as close as Johnson and Pawnee Counties near the Kansas-Nebraska border. It also still survives locally in the Missouri Valley of southern South Dakota, though it once ranged across essentially all of both Dakotas and even barely into eastern Montana.

-

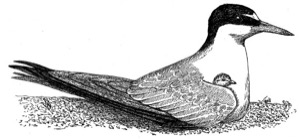

Interior Least Tern Sterna antillarum

athalassos FIG. 5

A specimen of the least tern was shot in what is now Washington County, Nebraska, on August 5, 1804. Lewis carefully described it, and he should have been given full credit for discovering the species, but it was not formally described until 1843, from a specimen obtained in the West Indies. As with the piping plover, the middle Missouri River has long been a major nesting region for this subspecies, which is now nationally endangered. Like the piping plover, the least tern evolved in an environment adapted to falling water levels during late spring, rather than today's generally increasing water levels of the middle and lower Missouri River in the spring, when water is released from upstream dams to facilitate summer barge traffic.

-

(Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus)

This hawk was not identified as such by Lewis, but he referred to seeing (while on the Oregon coast) the "hen-hawk," a species of hawk with a "long tail and blue wings," calling it the same kind as that found farther east. The male northern harrier has bluish wings and a distinctly long tail, and has been tentatively identified as the species in question, rather than the much rarer peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus). Since the harrier was not more specifically described as occurring in the Great Plains, it is not included as a positive occurrence.

-

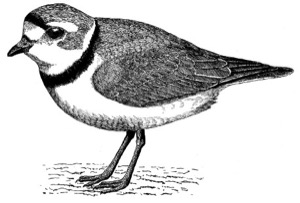

Piping Plover Charadrius melodus FIG.

6

Small plovers, described by Captain Clark as the "small species of Kildee," were observed to occupy river habitats as far upstream as the mouth of the Little Sioux River, present-day Burt County, Nebraska, or Harrison County, Iowa. It seems most likely that these birds were piping plovers, for which the middle Missouri River has long been a major breeding ground. However, the species was first officially described in 1824 on the Atlantic coast. The Great Plains population of piping plover is now nationally threatened.

-

Red-tailed Hawk Buteo jamaicensis

As with the northern harrier, this hawk was not identified as such by the expedition, but Captain Clark noted hawks along the shoreline of present-day Thurston and Burt Counties, which Swenk thought might have been this species. Since the red-tailed hawk is by far the most common breeding hawk of the central Missouri Valley, and is a permanent resident all the way north to North Dakota, it was almost certainly seen during the expedition's Great Plains phase. Red-tailed hawk populations have increased significantly in North America during the last four decades, the birds having benefited from improved federal protection and having learned to exploit foraging opportunities along superhighways.

-

Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius

phoeniceus)

Captain Clark observed large numbers of a "black bird" near Spirit Mound in Clay County, South Dakota (opposite Dixon County, Nebraska), on August 25, 1804. Swenk tentatively identified this species as the lark bunting (Calamospiza melanocorys). However, by August the lark bunting's breeding season is over, and males would be molting out of their nearly all-black breeding plumage and into a brown plumage. Other more common and permanently black-plumaged birds in that region are better possibilities, including various blackbirds and grackles. Gary Moulton has suggested that Clark observed the red-winged blackbird, which seems a much more likely choice, as by late August these abundant birds would be forming migratory flocks. One of the most numerous of North American songbirds, this species may number in excess of 100 million birds. However, although it probably increased greatly during the first half of the twentieth century, its overall population has been declining significantly over the past four decades as breeding habitats have been increasingly converted to agriculture.

-

Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus

Expedition members killed "several grous" during the time the group was camped just south of Council Bluffs in what is now Pottawattamie County, Iowa, on July 25, 1804. As Swenk concluded, these were almost certainly ruffed grouse rather than greater prairie-chickens or sharp-tailed grouse, given the wooded habitat along the river. Early records suggest that ruffed grouse once occurred along Nebraska's Missouri floodplain as far north as Omaha. They were extirpated from Nebraska and western Iowa by 1900.

-

(Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus or Eskimo curlew

Numenius borealis)

A shorebird called the "Jack Curloo" ("Jack" traditionally meaning small) was mentioned in a general way as having been seen by expedition members. It might be the whimbrel, a small curlew that was earlier known as the Hudsonian curlew. The even smaller Eskimo curlew also once migrated through the Great Plains in large numbers during spring, but it is now apparently extinct. Whimbrels still migrate in small numbers through the Great Plains but were unlikely to have been present during the expedition's passage up the Missouri River during the late summer of 1804, as their fall migration occurs mainly along the Atlantic coast. Whimbrels might also have been seen in eastern Montana the following spring, but they are now extremely rare in that state.

-

Whip-poor-will Caprimulgus vociferus

Captain Clark heard whip-poor-wills calling on September 6, 1806, in the vicinity of present-day Blair, Nebraska, and he had also heard them earlier during the trip upstream through Missouri and Kansas. September is remarkably late for whip-poor-wills to call, as this species has usually finished vocalizing by early August. It has apparently moved gradually northward during the past two centuries and now breeds as far north as southern South Dakota. However, rangewide whip-poor-will populations have declined significantly across North America during the last four decades, as have populations of the ecologically similar common nighthawk (Chordeiles minor).

-

Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo

Wild turkeys were killed and eaten by the expedition in Kansas and Nebraska. They were seen in large numbers on July 1, 1804, near present-day Leavenworth, Kansas, and one was killed on July 25, 1804, near present-day Council Bluffs. Another was killed the next day at the same camp, and others were taken on July 30 in what is now Washington County. Others were killed on August 5, 1804, on the Iowa side (now Harrison County) and one on August 9 on the Nebraska side (now Burt or Douglas County). Another was killed September 4 (now Knox County, Nebraska), and turkeys were seen above the mouth of the Niobrara River along the present Nebraska-South Dakota border (Boyd or Charles Mix County, respectively) on September 5. Others were killed in the same general boundary area on September 5 and 8. On the expedition's return trip through Nebraska wild turkeys were seen along the shorelines in present-day Nemaha and Richardson County. Although extirpated from the Missouri Valley of Nebraska and Kansas by shortly after the turn of the twentieth century, reintroduction efforts in both states have been successful. Wild turkey populations have increased significantly in North America during the last four decades, largely through releases and wildlife management practices.

-

Wood Duck Aix sponsa

The "summer duck" was quite familiar to Captain Lewis, who referred to it by that name on July 29, 1805, remarking that he had seen it as far west as the vicinity of Three Forks, Montana. However, unidentified ducks were also seen in some numbers during the river ascent through Nebraska, from as early as August 15, 1804 (present-day Dakota County), to September 5, 1804 (present-day Thurston or Burt County). As Swenk concluded, these most probably were wood ducks, which would have been common along the wooded Missouri River shorelines in late summer. Wood ducks were also reportedly seen in the vicinity of Great Falls, Montana, on June 19 and 23, 1805. Wood duck populations have increased significantly in North America during the last four decades, and their breeding range has expanded both to the west and north, partly as a result of the widespread erection of nesting boxes.

-

Bullsnake Pituophis catenifer

One of these nonvenomous snakes was killed on the Iowa side of the Missouri River near Soldier Creek (now Harrison County, Iowa) on August 5, 1804, when it was seen near a colony of bank swallows (Riparia riparia). One was also killed in what is now Bon Homme County, South Dakota, on September 5, 1804.

-

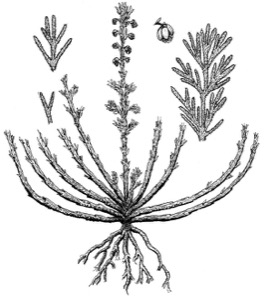

Buffaloberry Shepherdia argentea FIG.

7

A widespread perennial shrub whose edible fruits were cooked or eaten raw by Native Americans. The fruits were used in feasts celebrating a girl's arrival at puberty, and the plant's English vernacular name relates to the fact that the berries were once used to flavor bison meat. Collected September 4, 1804, probably in present-day Niobrara County, Nebraska. A newly discovered species.

-

Bur (Mossy-cup) Oak Quercus macrocarpa

The most arid-adapted and fire-tolerant of the oaks on the northern plains. It produces fairly large acorns, a valuable food for many wildlife species as well as humans, who often boiled the acorns to rid them of bitter tannic acid. The abundant tannin in oak bark, acorns, and galls was almost certainly used by Native Americans for tanning leather. Collected September 5, 1804, probably in present-day Knox County, Nebraska.

-

Curly-top Gumweed (Broad-leaved Gum Plant) Grindelia squarrosa

A widespread, weedy and aromatic perennial. Its gummy secretions were used by Native Americans as a medicine for bronchitis, colic, and asthma, and its boiled leaves used as a poultice. Pawnees used a decoction from the flowering tops to treat saddle sores on horses. The flower extract is sometimes still used as an herbal medicine for treating whooping cough and asthma. Collected August 17, 1804, in present-day Dakota County, Nebraska.

-

Horsetail (Scouring Rush) Equisetum

arvense

This widespread herbaceous perennial is part of a genus of primitive plants having about eight species on the northern Great Plains. All have silica granules in their stems, making them effective for abrasive scouring. The Omaha-Ponca tribe thus used horsetails for smoothing bow wood. Collected August 10, 1804, in present-day Burt County, Nebraska.

-

Meadow (Canada) Anemone Anemone

canadensis

A widespread perennial forb that produces a glycoside (ranunculin) and saponins, which have reputed medicinal properties when applied externally. Its use was generally limited to medicine men, and its root was regarded as strong medicine by the Omaha-Poncas and many other northern tribes. Pregnant Blackfoot women drank a tea from the boiled plant to speed delivery. Collected August 17, 1804, in present-day Dakota County, Nebraska.

-

Pasture Sagewort Artemisia frigida FIG.

8

A widespread perennial aromatic herb, used to bandage wounds, as toilet paper, for menstrual pads ("woman sage"), and to eliminate or at least cover the smell of dried meat. Collected September 2, 1804, probably in present-day Bon Homme County, South Dakota; also collected October 3, 1804, in present-day Porter or Sully County, South Dakota.

-

Purple Prairie-clover Petalostemon (Dalea)

purpurea

A widespread perennial forb. Native Americans steeped the bruised leaves and applied them to wounds, as Lewis noted on his original collection label. The roots were also chewed, and the stems were used for making brooms. Collected September 2, presumably in 1804, and probably in present-day Bon Homme County, South Dakota.

-

Raccoon Grape (Simple-leaved Ampelopsis) Ampelopsis

cordata

Like other grapes, the tiny fruits of this species are edible. Collected September 8, 1806, in present-day Washington County, Nebraska, and also September 14, 1806, in present-day Leavenworth County, Kansas.

-

Rigid Goldenrod (Hard-leaved Goldenrod) Solidago

rigida

The seeds of this widespread perennial forb species are often eaten by grouse and songbirds, and its flower heads are consumed by deer. Native American uses are not reported for this or other plains goldenrods. Collected September 12, 1806, in present-day Doniphan or Atchison County, Kansas, or Buchanan County, Missouri.

-

Rocky Mountain

Beeplant Cleome serrulata

A widespread, weedy annual, with an odor that is very attractive to bees. Native Americans ate the leaves and tender stems, and boiled the stems to make syrup that could be dried and later eaten or used as a black pigment. The Lakotas and Assiniboine also made a "medicine" for attracting bison prior to hunting them, by pounding roots of beeplant and leadplant, and rubbing the resulting materials on their clothing. The abundant if small seeds were also ground into flour. Collected August 25, 1804, in present-day Cedar or Dixon County, Nebraska, or Clay County, South Dakota.

-

Wild Four-o'clock Mirabilis nyctaginea

This is a widespread perennial forb whose vernacular name refers to the fact that it opens late in the afternoon, blooms all night, and wilts by the following morning. Its generic name means marvelous or strange, and its root was used by Native Americans for many medicinal purposes. The Lakotas boiled the root to treat fever, and it was also used as an apparently effective vermifuge. Among the Pawnees the dried root was ground up and used as a remedy for sore mouth in babies, and a root decoction was also used after childbirth to reduce swelling. The seeds and roots of at least some Mirabilis species contain the alkaloid trigonelline. Collected September 1, 1804, probably in present-day Bon Homme County, South Dakota; also collected October 3, 1804, in present-day Porter or Sully County, South Dakota.

-

Wild Rice Zizania palustris

Wild rice has long been an important source of grain for Native Americans. It occurs from the Sandhills wetlands of central Nebraska north sporadically to North Dakota. Collected September 8, 1804, in present-day Boyd County, Nebraska, or (less probably) in Charles Mix or Gregory County, South Dakota. A newly discovered species.

-

Wild Rose Rosa arkansana

A widespread native perennial shrub. The young shoots were used by Native Americans as a potherb, the petals were eaten raw, candied, or dried for use as perfume. The bark was smoked as a component of tobacco substitutes, and the leaves were used for tea or as decoctions to treat eye inflammations. The fruits ("hips") of roses are rich in vitamins A and C, as well as tannin, flavonol glycosides, and carotene. Collected September 5, 1804, in present-day Knox County, Nebraska, or in Charles Mix County, South Dakota. Also collected October 18, 1804, probably in present-day Sioux County, North Dakota.